“With the demise of the buffalo, Indian culture on the Plains changed forever. A new life would have to be shaped where once the buffalo had held the center. From the sacredness of the buffalo hat to the practicality of the buffalo chip, Cheyenne culture, like that of all Plains Indians, had evolved from a long association with the bison.”

— Alan Boye, Holding Stone Hands on the Trail of the Cheyenne Exodus

My fascination with bison began at age ten when my parents took our family on weekend excursions to Glacier National Park, Flathead Lake, or the National Bison Range passing through the Flathead Indian Reservation in western Montana. We would often visit the National Bison Range in search of bears, elk, bison, and other wildlife.

Learning to love wildlife developed into habit of adventure seeking that has stayed with me well into adulthood. Whenever I have time off, I visit the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge – home to over 330 species of wildlife — located ten miles northeast of downtown Denver. The hallmark species at the Refuge is the bison herd — now over 200 — that drew over three-quarters of a million visitors from 2021-2022.

Learning to love wildlife developed into habit of adventure seeking that has stayed with me well into adulthood. Whenever I have time off, I visit the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge – home to over 330 species of wildlife — located ten miles northeast of downtown Denver. The hallmark species at the Refuge is the bison herd — now over 200 — that drew over three-quarters of a million visitors from 2021-2022.

Estimates are that the bison numbered 30 million in North America. Where they once freely roamed, North America’s largest terrestrial mammal is now held in private ranches and farms and on public, nonprofit, government, and tribal lands. In summer 2021, the U.S. Department of the Interior transferred all land comprising the National Bison Range, more than 18,800 acres, to be held in trust for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation in Montana. This move marked the official return of Bison Range lands to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

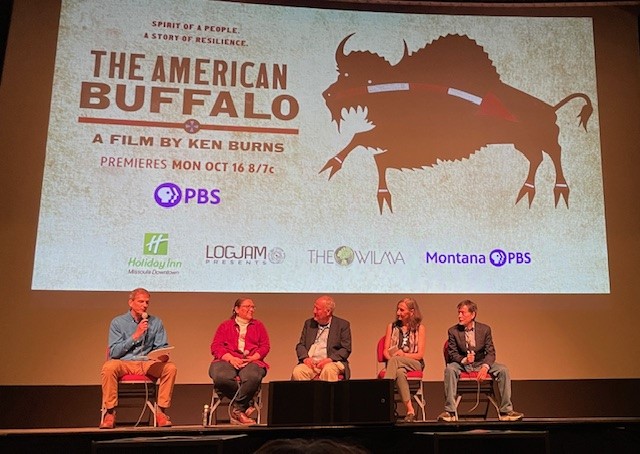

This week Ken Burns launched a new four-hour documentary called The American Buffalo – it premiered on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) October 16 and 17. The documentary tells the story of the strength and survival of the American bison, which had been driven to near extinction. Here’s how the film is promoted: “The American Buffalo is the biography of an improbable, shaggy beast that has found itself at the center of many of the country’s most mythic and heartbreaking tales. The series, which has been four years in the making, takes viewers on a journey of more than 10,000 years of North American history and across some of the country’s most iconic landscapes, tracing the national mammal’s evolution, and its significance to Indigenous people and the landscape of the Great Plains, its near extinction, and the efforts to bring the magnificent mammals back from the brink.”

This week Ken Burns launched a new four-hour documentary called The American Buffalo – it premiered on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) October 16 and 17. The documentary tells the story of the strength and survival of the American bison, which had been driven to near extinction. Here’s how the film is promoted: “The American Buffalo is the biography of an improbable, shaggy beast that has found itself at the center of many of the country’s most mythic and heartbreaking tales. The series, which has been four years in the making, takes viewers on a journey of more than 10,000 years of North American history and across some of the country’s most iconic landscapes, tracing the national mammal’s evolution, and its significance to Indigenous people and the landscape of the Great Plains, its near extinction, and the efforts to bring the magnificent mammals back from the brink.”

In June 2023, I attended a sneak preview of the film hosted by Montana PBS that was followed by a panel discussion with director Ken Burns, writer Dayton Duncan, producer Julie Dunfey, historian Rosalyn LaPier, and moderator John Twiggs. Four ten-minute clips from the documentary premiered to a packed crowd in the Wilma Theatre.

An enrolled member of the Blackfeet Tribe of Montana and Métis, Rosalyn LaPier is an environmental historian and ethnobotanist. Her knowledge, voice, wisdom, and perspectives were critically important to the Burns documentary. LaPier supports Native control and restoration efforts of the bison. A fierce advocate of Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous science, LaPier said, “The film really is two different stories. It’s a story of Indigenous people and their relationship with the bison for thousands of years. And then, enter not just the Europeans, but the Americans… that’s a completely different story. That really is a story of utter destruction.”

LaPier invited me to a preview on August 25 in Denver at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House. It was here that I visited backstage with LaPier and iconic storyteller Ken Burns in private as they ate dinner before the evening’s event. Following the preview LaPier said, “The greatest murder of animals in the history of the world happened here based on disparate value systems. The Indigenous people co-evolved with the bison. Bison have always lived with humans.” LaPier went on to say, “It can be repaired. Indigenous people have six hundred years of living with the bison.”

LaPier invited me to a preview on August 25 in Denver at the Ellie Caulkins Opera House. It was here that I visited backstage with LaPier and iconic storyteller Ken Burns in private as they ate dinner before the evening’s event. Following the preview LaPier said, “The greatest murder of animals in the history of the world happened here based on disparate value systems. The Indigenous people co-evolved with the bison. Bison have always lived with humans.” LaPier went on to say, “It can be repaired. Indigenous people have six hundred years of living with the bison.”

In my conversations with LaPier, we agreed that the future of the bison depends on intervention, and advocacy by tribal scientists, tribal communities, and tribal governments. The creation of ecosystems involves restoring the American bison to the American Serengeti – the Great Plains. LaPier believes that bison along with coyotes and wolves can survive if we create large enough spaces. Tribes are holding “homecomings” for bison and taking them back to tribal transfer, conservatorship, and cultural conservation. Reconnecting bison and tribes is a solution and efforts to build and restore bison herds on tribal lands are underway.

Another important event happening this week is the 2023 AISES National Conference in Spokane, Wash. AISES is helping to preserve the bison herds in the United States by supporting the current and emerging Indigenous scientists, wildlife biologists, conservationists, ecologists, and ethnobotanists who are needed in the nationwide efforts to restore bison to areas where they once roamed freely. These skilled professionals are critical to supporting education, outreach, restoration, and management of these magnificent mammals.

Not on our watch! AISES will do everything within our power to be an ally to the change makers — Native and non-Native — who are working on the frontlines to increase the bison populations and begin to heal the damage that was done over 200 years ago to our bison relatives. We must avoid the near erasure of the bison in North America for our cultural and spiritual healing.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Linked In

Linked In YouTube

YouTube